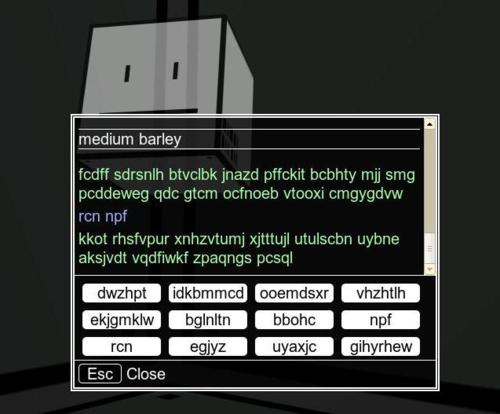

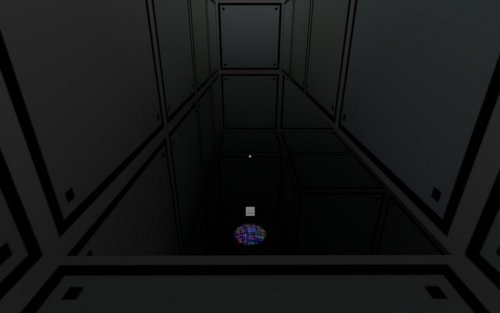

Unless something goes horribly wrong with the collision detection code, here is a perspective gamers rarely get of their favorite games:

That’s the view from far outside the pavo map. To save on drawing time, it’s usual for the renderer to leave the back sides of polygons undrawn, which is why you can see into the map at all. I personally find it a little creepy at times, like I’m wandering the walls between worlds or something.

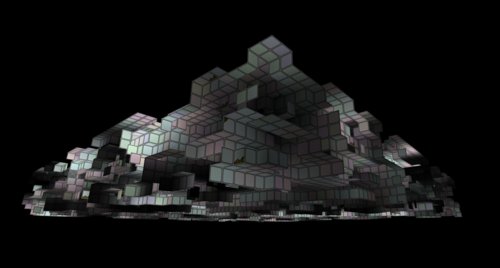

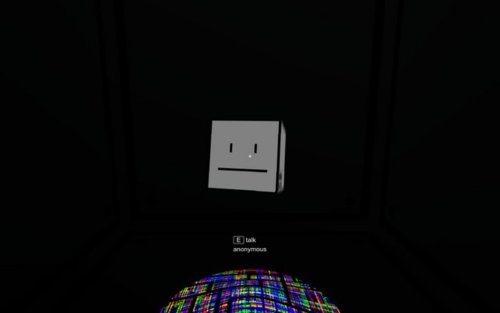

Here’s a top-down view of the same map:

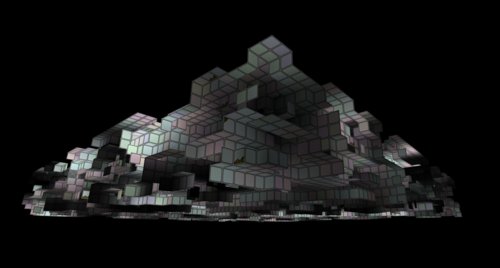

Where does all that structure come from? Well, I didn’t lovingly hand-craft each of the squares and slot them into place. I’m patient, but not that patient. Instead, I used the Noise3D object in the Foam library to generate it procedurally.

field = new FOAM.Noise3D(seed, 1.0, source.x, scale.x, source.y, scale.y, source.z, scale.z);

At first, I found the concept of a three-dimensional noise field hard to grasp. I can visualize a 1D noise field as a wobbly line, and a 2D noise field as bumpy surface. Each of these is created by rolling up a sequence of random numbers, and finding values that fit smoothly between adjacent numbers in the sequence. This is called interpolation.

In the 1D case, I have a noise function y = f(x), and can create my wobbly line by graphing y against x. The 2D case gives me a noise function y = f(x, z) for which I graph y against x and z to generate my bumpy surface. (I’ve written previously about using the Noise2D object to create such a surface for Fissure.) Both cases create surfaces via the displacement of points along a “flat” figure such as a line or a plane.

In three dimensions, we have to think about the noise field differently. It can’t be a displacement, because that means we would be displacing points on a cube into the 4th dimension. That might give us something visually interesting but hardly comprehensible. Instead, I think of the 3D noise object as a density function–a measure of the solidity of space at a particular point. Using that interpretation, I can assign a critical threshold that will divide “solid” space from “empty” space, and create a function that tells me which is which.

this.inside = function(x, y, z) {

return field.get(x, y, z) > 0.5;

}

The function is called inside because it tells me if I’m inside the empty space–our game space. (Not much fun playing inside solid space, as you can’t move.) My 3D noise function is normalized to produce values from 0 to 1, and I’ve found that using the mean value of 0.5 as the threshold yields the most useful spaces.

So we have a function that tells us where the surface is. How do we turn that into an actual thing that we can see? I’ve written a simplified version of the marching cubes algorithm:

for (x = -RESOLUTION; x <= LENGTH.x; x += RESOLUTION) {

nx = x;

px = x + RESOLUTION;

for (y = -RESOLUTION; y <= LENGTH.y; y += RESOLUTION) {

ny = y;

py = y + RESOLUTION;

for (z = -RESOLUTION; z <= LENGTH.z; z += RESOLUTION) {

nz = z;

pz = z + RESOLUTION;

o = this.inside(x, y, z);

p = this.inside(x + RESOLUTION, y, z);

if ( !o && p ) {

... draw x-aligned square ...

}

if ( o && !p ) {

... draw x-aligned square (alt winding) ...

}

p = this.inside(x, y + RESOLUTION, z);

if ( !o && p ) {

... draw y-aligned square ...

}

if ( o && !p ) {

... draw y-aligned square (alt winding) ...

}

p = this.inside(x, y, z + RESOLUTION);

if ( !o && p ) {

... draw z-aligned square ...

}

if ( o && !p ) {

... draw z-aligned square (alt winding) ...

}

}

}

}

(The alternate winding refers to whether we’re drawing the figure clockwise or counter-clockwise. In order to make all polygons front-facing, we have to switch the winding order depending on whether we’re going into or out of the surface.)

Basically, it’s just a set of nested loops, each iterating through an axis in 3-space. Whenever I pass through the surface (represented by the noise function and threshold), I draw a square of the proper orientation. Put all those squares together and you have a surface. It’s more blocky than bumpy. There are more advanced algorithms you can use to generate a bumpy surface, but this runs fast enough in Javascript and doesn’t require an advanced shader model.

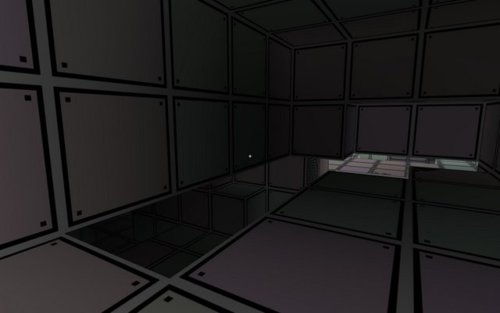

Note that the surface you generate from this noise function will have no border as the function itself is defined for all (x, y, z). If you want a border, you can create one with ease by amending the inside function:

this.inside = function(x, y, z) {

if (x < LLIMIT.x || y < LLIMIT.y || z < LLIMIT.z ||

x > ULIMIT.x || y > ULIMIT.y || z > ULIMIT.z)

return false;

return field.get(x, y, z) > 0.5;

}

That’s how I generate the solid walls that border the pavo game space.

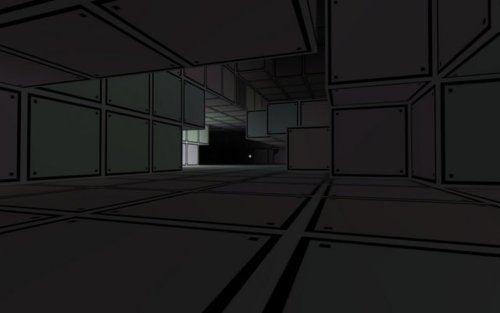

Another trick I used in pavo involves the lighting. In Fissure I placed a single light at the camera position to light the way for the player, but for pavo I wanted lights all over the place. Dynamic lighting is computationally expensive, and probably an unecessary luxury for a small browser game, but static lighting is cheap and easy. My favorite. Can I use a noise field to generate this? You bet I can.

light = new FOAM.Noise3D(seed, 1.0, source.x, scale.x, source.y, scale.y, source.z, scale.z);

...

light.gets = function(x, y, z) {

return Math.pow(light.get(x, y, z), 2);

};

...

mesh = new FOAM.Mesh();

mesh.add(program.position, 3);

mesh.add(program.texturec, 2);

mesh.add(program.a_light, 1);

...

mesh.set(x, y, z, t0, t1, light.gets(x, y, z));

I created a noise field to represent the light intensity at any point. To emulate how light intensity diminishes as the square of the distance, I extended the noise object with a new method. When I add a vertex to the mesh, I assign the calculated light intensity to it. The GPU will generate an interpolated light value that I can use in the fragment shader.

The same technique can be applied to objects moving through the space, so that they will appear to be slipping through areas of light and shadow. And there you have it. I’m targeting pavo for an end of year release, though it may slip, given the holidays.